Episodes

Monday Sep 25, 2023

Monday Sep 25, 2023

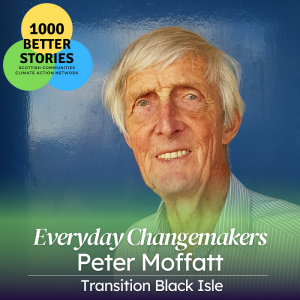

Today’s Everyday Changemaker is Peter Moffatt, Transition Black Isle trustee and a man behind its website. Our Story Weaver, Kaska Hempel, caught up with him at SCCAN’s Northern Gathering in Inverness on the 16th of September.

Credits:

Interview and audio production: Kaska Hempel

Resources:

Transition Black Isle https://www.transitionblackisle.org/

Transition Network (worldwide) https://transitionnetwork.org/

Transition Together (Britain) https://transitiontogether.org.uk/ (SCCAN is part of this project/network)

Transition Black Isle Million Miles Project 2012-15 https://www.transitionblackisle.org/million-miles-project.asp

Million Miles Project in The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/23/carbon-cutting-transport-scheme-helping-black-isle-go-green-scottish-highlands

21 Stories of Transition (book produced for COP21), including a story about the Million Miles Project https://transitionnetwork.org/resources/21-stories-of-transition-pdf-to-download/

Highland Good Food Partnership https://highlandgoodfood.scot/

Highland Community Waste Partnership https://www.keepscotlandbeautiful.org/highland-community-waste-partnership/

James Rebanks English Pastoral https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/sep/03/english-pastoral-by-james-rebanks-review-how-to-look-after-the-land

Gorge Monbiot Regenesis https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jun/05/regenesis-by-george-monbiot-review-hungry-for-real-change

Transcript

[00:00:00] Kaska Hempel: It's Kaska, your Story Weaver. What a weekend it's been. Still buzzing after our members Northern Gathering on the 16th of September. I met some amazing people on the day and workshopped all sorts of ways in which stories and storytelling can help us all think about a better future for our communities.

As always, there was simply not enough time to chat to everyone about everything. But since I already travelled all the way to the north, I also took time to visit several amazing community groups around Inverness for Everyday Changemakers interviews. And honestly, I can't wait to share those soon in the podcast as well as a wee place based audio tour I'm going to put together for you.

I road tested the tour by cycling around the project locations and I think the stories will make for a fantastic way to explore Inverness on a bike, either in person or online. But today I wanted to share my chat with Peter Moffat from Transition Black Isle, which is based on Black Isle, just north of Inverness.

As usual, you can find out more about the stories and resources behind this community group from links I popped into the show notes for you. I met Peter at the gathering itself, where he was holding an information stall for his group. And at lunchtime, we stepped outside the Merkinch Community Centre to record our conversation.

[00:01:26] Peter Moffatt: I'm Peter Moffatt. I'm one of the trustees of Transition Black Isle.

I have been since 2015. I live at the eastern end of the Black Isle, not far from Muir of Ord, two fields away from the Black Isle Dairy, which is a very, it's one of the few dairy farms in the north of Scotland. It has an enterprising young owner who runs a farm shop.

[00:01:51] Kaska Hempel: Tell me about a favourite place where you live.

[00:01:55] Peter Moffatt: There's a walk we do just round the fields from the back of the house, which goes along at one stage, an avenue of beach trees looking over the fields towards the Beauly Firth. And it's a wonderful view. And it's just walking around the fields, and it's great.

The other way we sometimes go is down over the fields to Conon Bridge, and then along the River Conon. There's a lovely old graveyard a mile or two along there, which not many people know about. But it's a wonderful place to go and think about the people who've gone before you basically, and a very pleasant, enjoyable walk.

[00:02:32] Kaska Hempel: How come you got involved in community climate action? What's been your journey?

[00:02:37] Peter Moffatt: I can't think of anything particular that sort of started me off.

I joined Transition Black Isle as a result of talking to somebody at a stall they were running at an event in Muir of Ord, which I think was something to do with a transport proposal and went on from there really. I admitted to the fact that I had worked with computers and I promptly got captured as it were because the person that currently ran the website lived in Aberdeen and wasn't very active.

So first thing I did was become responsible for editing the Transition Black Isle website, which i've been doing ever since. I'm not sure how many people actually look at it regularly, but I do try and keep it updated with information about climate change and climate activities and government policy and the council, what the council's doing.

I quite enjoy it, but I can't go on doing it forever, obviously. But there's nobody looking... To come and take over.

[00:03:31] Kaska Hempel: What about before you joined Transition? Were you interested in climate issues or environmental issues before then?

[00:03:38] Peter Moffatt: I can't remember. I've always been interested in the sort of countryside issues. My father was a farm manager, so I grew up interested in farming and used to go and work on a cousin's farm during the summer holidays when I was a student and on the farm at home as well.

So I suppose that's interest in nature and the outdoors and I've also been interested in mountaineering all my life. Where there's concern with climate change, I suppose it grew up, as it grew up generally, not very long ago. Despite the fact that people have been warning about it for the last 50 years, people only generally started to take notice relatively recently.

I remember being particularly struck by Greta Thunberg's initial school strike for climate as it was when she sat down outside the Swedish parliament. And she was on the website as soon as she did that, and I've been supporting her as strongly as I can ever since. So setting a fine example.

I don't know honestly where my personal concern with climate change as such began. Possibly as a result of joining Transition Black Isle.

[00:04:50] Kaska Hempel: When I say transition movement, what's the first thing that comes to your mind?

[00:04:55] Peter Moffatt: The idea of trying to move from the status quo business as usual consumerist society to a more sustainable way of life basically. And that was the founding idea of the transition movement. When it began in Totnes, how much transition is actually taking place. Some of the ideas that they had aren't really being applied, I don't think.

There were transition groups were supposed to have energy reduction plans which would progressively reduce the amount of energy consumed in the local area and change its nature. So it was more from renewables. That's not really happening, which is not to say that Transition Black Isle and other groups, whether they're transition groups formally or not, aren't doing a lot of good work.

They are and there's an amazing number of them, but I can't help feeling that for all the good they're doing, you know, merely scratching the surface of what actually needs to be done.

[00:05:53] Kaska Hempel: What makes you the proudest in terms of achievements? of Transition Black Isle.

[00:05:59] Peter Moffatt: Major achievement was something they called the Million Miles Project which was a project aimed at reducing car use on the Black Isle by a million miles over a period of two years I think the project ran and it was amazingly successful, a lot of support.

It actually became the number one story in a book of 20 stories published by the transition movement, I think for one of the COP climate conferences. And we were quite proud of that. Apart from that, recently we are involved as partners in two very important co operative ventures. One is the Highland Good Food Partnership, which grew out of a series of online discussions which were held about two years ago I think.

The other more recent initiative is something called the Highland Community Waste Partnership, which involves eight groups throughout the Highlands. Which is led by Keep Scotland Beautiful and is aiming to raise awareness of waste and reduce waste, particularly food waste, in local communities.

A lot of good work being done. How widely it's being recognised, I'm not sure.

I mean, if you ask your average person on the Black Isle about the Highland Community Waste Partnership, I'm not sure they'd have heard of it. But perhaps that's because we're not publicising it well enough. But there is a lot of hard work being done.

[00:07:35] Kaska Hempel: Who or what inspires you personally?

[00:07:39] Peter Moffatt: That's difficult. Greta Thunberg for one. Talking about food and farming. James Rebanks. Excellent, fascinating book. English Pastoral I think it was called.

He is trying to recognise the sort of traditional values in farming as it ought to be practiced. Involved in the landscape and the countryside, he's in the Lake District, so it's obviously a certain type of land, sheep farming, which some people would say we should do away with, but if it's there, then he seems to set a fine example of how to do it in the right sort of attitude to the land and so on.

Somebody else I would mention is George Monbiot, writer and journalist and activist. Everything he says is pretty sensible. Some people are a bit dubious about his idea that we should replace all beef and dairy farming with industrially fermented protein generated from microbes, fed on carbon dioxide and hydrogen, which apparently you can eat.

It doesn't sound, it would be very appetizing, shall we say. But the chances of doing away with the entire meat and dairy industry, which people say we need to do in order if we're going to reduce environmental damage and feed people adequately, is well, it's a big ask and, it's difficult to see how it could ever come about.

I was just reading Tim Spector saying the same thing, basically, about the need to drastically reduce the amount of land devoted to producing crops to feed cattle for beef.

And we should all be eating more plant food instead. Which is undoubtedly true and unlikely to come about, unfortunately, which is one of my reasons for not being a climate optimist.

[00:09:31] Kaska Hempel: Since we're talking about meat and not eating meat, do you have a favourite vegetarian or vegan dish?

[00:09:36] Peter Moffatt: I make something which is called by the uninviting name of Veggie Grot. Which is in fact a vegetable it's a sort of... vegetable crumble, really with a sort of cheese and breadcrumbs topping. And it contains whatever vegetables come to hand, lightly cooked in the oven. It's popular with our friends.

I take it to mountaineering club meets and they all eat it eagerly enough. I'm not completely vegetarian, i'm certainly not vegan, but the idea of a vegan cheese or vegan sausages, I find difficult to accept. I know they exist. All our sandwiches today were vegan, I'm told. But we don't eat a lot of meat.

My wife and I are largely sort of 75 percent vegetarian, I would say, at least. And I like vegetables. I grow vegetables in the garden. And it's very satisfying to eat your own produce.

[00:10:25] Kaska Hempel: Where in the world are you happiest?

[00:10:28] Peter Moffatt: Where am I happiest? In a sunlit wood, preferably with a burn flowing by, or on the top of a Scottish mountain.

[00:10:42] Kaska Hempel: Now the final question, I always ask people to imagine the place they live in, ten years from now.

Imagine that we've done everything possible to limit the impact of climate change and create a better and fairer world.

And share one memory from that future with our listeners.

[00:11:02] Peter Moffatt: Quite honestly, I think it will be very little different from what it is now. If, some of the ideas that have been proposed in the local place plan that is currently being prepared for the Black Isle and will be presented to the council at the end of this month. If some of them were to come to fruition, then the Black Isle would have a better transport system.

It would have lots of affordable housing available for local people. It would have more local food production. Better care for old people. And safer cycle routes and so on. Transition Black Isle has been working for years on an active travel route, cycle path basically, between Avoch and Munlochy, and we have been frustrated.

It's a question of getting a hold of the land, and there has been reluctance in some quarters to make land available.

[00:12:03] Kaska Hempel: And if you can share one sound or smell or taste of that future, what would it be?

[00:12:08] Peter Moffatt: I would like to think it was the sound of Curlews and we used to hear them over the fields outside the house. We were in Shetland a little while ago looking out over the pasture which should have been busy with Curlews and Lapwings and there was nothing there at all. Whether anything is likely to change to the extent that these birds become more numerous than they are at the moment, I don't know.

It's unlikely, but it would be nice. I would love to hear Lapwings calling over the fields outside our house on a regular basis.

[00:12:38] Kaska Hempel: I'm going to ask you if there's anything else that you wanted to add for our listeners.

[00:12:44] Peter Moffatt: If you're interested and concerned about climate change and so on, just think whether you could make that little bit extra effort and volunteer for organisations like Transition Black Isle. There are plenty of other organisations on the Black Isle and elsewhere. Offer to volunteer, offer to become a trustee maybe and take a bit of responsibility.

It's not very much. Put your good intentions into practice. Transition Black Isle has an online newsletter with a subscriber list of about 480 people. It has a membership of about 150. It has six trustees, needs more, and it is sometimes difficult to get people, especially young people, to volunteer to help with activities.

There's a serious lack of young people coming forward, whether it's because they think it's an old fogey's group. I don't know. But we need more involvement by people who are obviously concerned, but just need to take a step forward and put that concern into voluntary action and actually help the climate movement on its way.

Friday Sep 01, 2023

Friday Sep 01, 2023

Kaska Hempel, our Story Weaver, interviews Tom Nockolds, who is one of the people behind the community-driven retrofit project, Loco Home Retrofit, based in Glasgow.

This episode complements video recordings of presentations from the "SCCAN Member Networking and Skillshare Meet up: Talking about Retrofitting", which took place on 25 August 2023. You can find them on SCCAN YouTube channel.

Credits:

Interview and audio production: Kaska Hempel.

Resources:

SCCAN YouTube channel with the recording from the members skillshare on community-led retrofitting, 25th August 2023: https://www.youtube.com/@scottishcommunitiesclimate6914/videos

Loco Home Retrofit https://locohome.coop/

SEDA Retrofit conference, 15-16 September 2023 https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/seda-conference-2023-progressing-retrofit-comfort-health-affordability-tickets-692329465067

Transcript

[00:00:00] Kaska Hempel: Hello, it's Kaska, one of your Story Weavers. Last Friday I attended one of SCCAN's Member Skillshares. Focused on a truly wicked problem of retrofitting our very energy inefficient Scottish homes.

[00:00:16] Kaska Hempel: Our housing stock seems to be one of the worst in Europe for energy efficiency, which makes it unhealthy, uncomfortable, and expensive to heat. Yet there's not been nearly enough progress made on this so far by our governments.

[00:00:32] Kaska Hempel: Very frustrating indeed. So, I was impressed how a couple of Scottish grassroots organisations are taking matters in their own hands. By treating this as a community problem or rather a community driven solution, and this way

[00:00:48] Kaska Hempel: Moving things ahead locally.

[00:00:50] Kaska Hempel: This inspired me to interview one of the presenters, Tom Nockolds, who's behind one of the community driven projects, Loco Home Retrofit in Glasgow. For more details on the retrofit projects themselves, you can watch recordings of the Skillshare on SCCAN's YouTube channel as soon as they're processed. And as usual, we put all the other relevant links in the episode notes for you.

[00:01:15] Kaska Hempel: And if you'd like to delve into the nitty gritty of holistic approach to retrofitting, have a look at the Scottish Ecological Design Association Conference on the subject, which is taking place in Glasgow and on Zoom on the 15th and 16th of September.

[00:01:32] Kaska Hempel: But for now, let's go back to our Everyday Changemakers story and find out what makes Tom tick.

[00:01:41] Tom Nockolds: I'm Tom Nockolds. I live in Glasgow and I'm the co-founder and co-executive Officer of Loco Home Retrofit. Loco Home Retrofit is a cooperative, as well as a community interest company whose mission is to decarbonise homes in Glasgow. And we're very focused on privately owned households. We operate in the space of retrofit, which is a bit of a technical jargonistic term. Simply means refitting, energy efficiency, and low carbon heating into existing buildings. And our mission is to make better retrofit more accessible for more people in Glasgow.

[00:02:29] Kaska Hempel: Great. That sounds amazing. why Loco?

[00:02:33] Tom Nockolds: We struggled with a name for a little while. I was saying to Chris, co-founder, I was saying to Chris, you know, let's not give ourselves a boring name like Glasgow, Retrofit Co-op.

[00:02:47] Tom Nockolds: And he was really on board with that idea. And we eventually settled on Loco because it's a bit of a play on low carbon 'cause we are a climate change action organisation, but it's also about local community. And thirdly, and very much last and least, we did acknowledge that Loco does have a meaning in some other languages. And we wanted to acknowledge that what we were doing was a little bit crazy, you know?

[00:03:18] Kaska Hempel: Because

[00:03:18] Kaska Hempel: Loco is Spanish for a bit mad, isn't it?

[00:03:22] Tom Nockolds: It might be a mild way of putting it, so I'm a bit hesitant to focus too much on the Loco with that definition. Mostly it's a play on low carbon, local community.

[00:03:33] Kaska Hempel: Yeah, it reminds me of Locomotive.

[00:03:35] Kaska Hempel: So it's like putting something in motion as well.

[00:03:37] Tom Nockolds: That's right. Exactly. We're all about getting people moving on their retrofit journey.

[00:03:42] Tom Nockolds: We also grappled whether or not we would lean into the jargonistic term retrofit or try and avoid it. And obviously we decided to lean into it. So it is a bit of a challenge to get out there and start talking to people about retrofit, and we need to approach that carefully, but it's in our name, and that for us is a bit of an icebreaker.

[00:04:03] Kaska Hempel: Great way to start a conversation.

[00:04:06] Kaska Hempel: Tell me maybe about a favourite place where you live, or part of the project that you are involved with. That's your favourite part.

[00:04:15] Tom Nockolds: So I've been living in Glasgow for three years. You hear from my voice that I'm Australian. And I've only been living in Scotland for four years. I live in the south side of Glasgow. I live in a suburb called Strathbungo, which is actually a very small suburb. Many people have heard of it. It's got a very high profile. But it's very small and the way that I like to describe it is that particularly my part of Strathbungo, 'cause I live in a tenement building, is sandwiched between two of the largest tenement areas in Glasgow, Pollokshields and Govan Hill. And I live on a road that is one of the main thoroughfares between these two neighbourhoods.

[00:04:59] Tom Nockolds: And I myself live in a tenement area. It's a very diverse, vibrant neighbourhood. Probably the most ethnically diverse neighbourhood in Scotland. There's a huge amount going on. So when I walk out my door, there's a lot on offer. A lot of really interesting shops, lots of cool bars and cafes and things like that. But just a lot of people who bring a lot of different things to the local area. And in particular, I live very close to Queens Park, and Queens Park is one of the best parks in Glasgow in my opinion.

[00:05:38] Tom Nockolds: It's not just a Victorian era park, we're sort of parading formal gardens, but it's got a wooded area and you can just lose yourself and escape the really urban environment that exists when there's tenements. And the thing that I relearn every time I go into Queens Park is that you've got to never forget to regularly go in and be amongst the trees 'cause they have this incredible ability to de-stress you. And then, you know, later that day or the next day, I've completely forgotten.

[00:06:10] Kaska Hempel: Yes, regular detox, so important. It's so fortunate that you've got that on your doorstep.

[00:06:14] Tom Nockolds: Yeah. But a really built up urban environment with a lot of vibrancy, and very close to this amazing outdoor area of Queens Park with views over the city trees and yeah, just beautiful, beautiful location.

[00:06:31] Kaska Hempel: That sounds pretty amazing. Now, if you could briefly tell us about why you got involved in community action or climate action in this project that you set up here.

[00:06:44] Tom Nockolds: Well, for me it's always been there, this sort of voice inside of me about making a positive contribution and in particular an environmental bent. I grew up in a suburb of Sydney in Australia, suburb I grew up in, Balmain was traditionally a very working class suburb and was one of the places where the Australian Labor Party emerged. So really, I grew up immersed in an environment where labour struggles and class struggles were a feature.

My parents were very aware of this, even if they weren't themselves from that background. My dad was an academic, for example. But I didn't move into that space. I got on with life and struggling as a young adult to find my way. But it was when I was in my late thirties. I found myself working for multinational law firm in the Sydney office. Law firms are interesting. They occupy the top floors of the nicest buildings. It's a really nice working environment, and you get to work with some really amazing, intelligent people.

[00:08:00] Tom Nockolds: But it became increasingly apparent to me that I was working for the bad guys. This particular event took place where a memo went round to all staff and it said something like, you've heard about fracking and coal, steam gas extraction from the media, come along and find out what it's all about. And it was sent to all staff. There were separate mailing lists for just the legal staff. 'cause I wasn't a lawyer, I was just helping with IT and sustainability projects. So it seemed like, it was a genuine, let's explore this issue.

But when I went along, to my horror, it was actually a session for lawyers on how they could successfully navigate their client's coal and steam gas exploration license through the regulatory regime to maximize chance of success. And that for me was the big moment where it was brought up right up into my face. You're doing the right work for the wrong organisation. And I was in a fairly comfortable position at the time. I'd never been a wealthy person, but my wife had just finished a year of study and we knew that we could survive on one income and she'd got her job back. And I quit my job. Gave them the minimum amount of notice and walked out the door, and I didn't have anywhere I was going to.

[00:09:24] Tom Nockolds: I just threw myself headlong into volunteering. Lots of volunteering in my local community and for initiatives across the city. And very quickly I realised that the thing for me was community energy. And within less than a year, I was part of the team at a small workers co-op, co-founded by two amazing women. And that organisation is called Community Power Agency. And to date, they remain Australia's only dedicated support organisation, helping communities develop energy projects. I did a lot of volunteering, for one group in particular, Pingala. And, we put solar panels on the roof of craft breweries across the city, among other things. And that was lots of fun. And, yeah, I basically consider that ever since 2013, my career has been working in the field of community energy. It's just that in 2020 thereabouts, I shifted my focus from installing new energy generation to decarbonising projects. So my work with Loco Home Retrofit is still community energy, but it's about decarbonising. And reducing energy consumption.

[00:10:39] Kaska Hempel: The flip side of our energy problem, isn't it? Thank you for sharing that.That's pretty drastic journey, but, it feels like you're in a much better space right now.

[00:10:44] Tom Nockolds: I mean, it was the best decision I've ever made in my life, career wise. And I rapidly found myself working with the most amazing people, doing the most rewarding work. Feeling like I was making a big contribution, never earning less money. It's been wonderful.

[00:11:11] Kaska Hempel: Brilliant. Hey, sales pitch for community work. Great. Now you've already defined retrofit for us when you're introducing your project. But what does it mean to you?

[00:11:23] Kaska Hempel: Yeah, I think for me, the main thing that I think about and feel when I hear the word retrofit, it's about making our existing buildings fit for the future. We're gonna need to make our homes a lot more resilient because of increasingly you know, violent weather. And before that, we need to make sure that they're first of all well maintained, but also in the future we're gonna need to make sure that our houses are not causing damage to the environment, such as contributing to climate change through carbon emissions, and healthy spaces for the occupants. So when I hear the word retrofit, I think of homes that are fit for the future, that are well maintained and resilient, that are healthy, comfortable and zero carbon.

[00:12:27] Kaska Hempel: What advice would you give to people who want to learn more about retrofit and how communities can get involved in this?

[00:12:36] Tom Nockolds: First of all, one thing that I don't think I've explained is that we are a particular type of retrofit organisation. We're a local community intermediary. And let me just sort of unpack that a little bit.

[00:12:47] Tom Nockolds: We firmly believe that because retrofit of homes is going to be difficult for any given homeowner, disruptive and expensive, that it's vital that people are hearing from people in their own community about what the benefits of retrofit will be, how to go about it. It's also relevant that buildings are subtly different in different areas.

So in Scotland, for example, in Glasgow, we've got traditional buildings built out of sandstone using particular techniques. Whereas in Aberdeen, they've got traditional buildings built out of granite using specific techniques. So that local context really does matter. And we also know that from looking at previous programmes such as the Green Deal, the Ill-Fated Westminster programme. Top down, centralised government approaches to energy efficiency and environmental behaviour change generally don't work.

[00:13:59] Tom Nockolds: I mean, they're necessary. They're a necessary ingredient and piece in the puzzle, but they don't actually work in terms of delivering the outcomes, achieving their goals, and recognising the needs of local people, motivating the local people to take action. So that's a local and community piece. And intermediary refers to the fact that there's simultaneously a lack of demand, a lack of households who are wanting to retrofit their homes. And there's also a lack of supply. There's lack of installers, tradespeople that have that specific knowledge about taking a whole house approach to go much deeper and get a home onto zero carbon heating. And so we think the best type of organisation to bridge the gap between homeowners and the supply chain is a locally based organisation who's rooted in the community.

[00:14:57] Tom Nockolds: So your question was, what advice would we have to someone starting out on this journey? First piece of advice is understand that need to find a way of embedding yourself in the community. I'm kind of thinking you are from the local community, and that gives you the greatest strength to be able to connect with all of the diverse aspects of what makes up that local community. And you need to do that in order to be successful. You don't necessarily need to have the technical skills, 'cause those technical skills are transferable. But it's the more difficult work is building the community connections between yourself and your organisation and all the different groups and all the individual householders. That's actually the difficult work. That'd be very difficult for an external organisation to get into focus on the community organising aspect without being blind to the technical skills that you need that you can potentially bring in from elsewhere.

[00:15:59] Kaska Hempel: Where in the world are you happiest?

[00:16:04] Tom Nockolds: it's funny, there's two places where that's the case. The one which is most obvious to me, is I grew up in a house which had a fairly open door policy, and we weren't a big family by any stretch. My parents were effectively migrants to Sydney and I'm the youngest of three, but nothing makes me happier than being in my home that's full of people, family and friends.

[00:16:36] Tom Nockolds: We had the great privilege of hosting Christmas a couple of years ago in our house, and the place was insanely full of people. It was stressful and noisy and hectic, but it confirmed something I really definitely already knew is that I'm happiest when my house is full of people. The second place I'm happiest is when I'm out in nature and in particular amongst trees.

[00:16:58] Kaska Hempel: For this last question, I ask everybody this, is for you to imagine the place you live in now, 10 years from now, and imagine that we have all done everything possible to limit the effects of climate change and make it a fairer and better place to be.

[00:17:17] Kaska Hempel: Here in Scotland, and you look around you 10 years from now,

[00:17:22] Kaska Hempel: share one impression or memory from that future with us.

[00:17:27] Tom Nockolds: The first thing is that the neighbourhood is a lot greener than it currently is. There's a lot more trees right in the heart of the urban environment, and that's because space has been made for them. The second thing is that it's a lot quieter. That's because trees have a dampening effect on sound.

[00:17:49] Tom Nockolds: But also because one of the main ways that space has been found for them is by replacing many journeys that are made by car with quieter, lower carbon, more sustainable forms of active travel. There's a lot more people walking and riding bicycles around. There's probably a lot more of those electric scooters too.

[00:18:10] Tom Nockolds: But the point is it's a lot quieter. And then the third thing is, I wouldn't say there's more people on the street, but there's more vibrancy around that. There's more people speaking to each other, saying hello to each other. So I consider that one of the main reasons why I'm doing the work is to build community. I'm not saying community doesn't exist in any given place. It does. I'm just saying I think our communities need to have stronger links, stronger connections. People need to know each other. That's one of the most important aspects of resilience as we step into a really uncertain future. So that's my vision. People know each other, well connected. It's quieter and it's definitely a lot greener.

[00:18:50] Kaska Hempel: Is there anything else you would like to share with the listeners that we haven't covered?

[00:18:55] Tom Nockolds: I think it's essential that we reduce carbon coming from our homes and I'm definitely very sceptical about any message around decarbonisation that it's all about individual choice. It's not all about individual choice. This has got to be about systemic change and about individual choice. One of the most important things we can do as individuals, whether we're renters or homeowners, is to be aware of just how much carbon is coming from heating our homes, homes in this cold climate of Scotland, and to demand that something be done about that.

Now, if you're a renter, the best thing you can do is to join a tenants union and speak to your landlord about them making your home more energy efficient and moving towards zero carbon heating. If you're a homeowner, the best thing you can do is to get yourself onto a having a whole house plan for retrofit. And that's the sort of thing our organisation can deliver. Now, if you're not in Glasgow, it's really worth considering whether or not you and some other local people should be establishing a local retrofit intermediary. Ideally structured as a co-op so that you can ensure that it's democratic, locally owned and the benefits are staying local so that you can start moving all of the homes in your area forwards on a journey towards zero carbon, getting those homes fit for the future.

[00:20:19] Kaska Hempel: Yes lets do it. Thank you so much.

[00:20:26] Tom Nockolds: Thanks Kaska for having me and yeah, it's been a real pleasure to chat.

Monday Aug 14, 2023

Monday Aug 14, 2023

Listen to an inspiring example of work by a tranditional storyteller in residence, helping community of Fittie in Aberdeen come together and face the past, present and future of the place where they live and love. Story was developed and perfomed by Cara Silversmith, with an introduction from our Story Weaver Lesley Anne.

Resources

Cara Silversmith's website: https://www.carasilversmith.com/

Cara's reflection on developing this story on her own podcast, "What of the Ground we’re standing on”: https://whatoftheground.podbean.com/e/commissioned-stories-honouring-truth-and-telling-stories-with-love/

1000 Better Stories Member of the Month: Fittie Community Development Trust https://sccan.scot/blog/member-of-the-month-the-fittie-community-development-trust/

Safe Harbour, Open Sea project https://www.openroadltd.com/projects/culture-collective/

Friday Jul 21, 2023

Friday Jul 21, 2023

Today Roz Littwin reads "Long Live Lenny", her short story creatively exploring the good work of the Edinburgh Remakery.

Roz’s story was originally published on the 1000 Better Stories blog and funded by one of our storytelling mini-grants. The grants fund contributions to 1000 Better Stories Blog and Podcast. They are open for applications now with a deadline at the end of July and another one at the end of October. Get in touch on stories@sccan.scot to find out more.

Credits:

Roz Littwin - text, recording and narrationKaska Hempel - production

Resources:

Edinburgh Remakery https://www.edinburghremakery.org.uk/

1000 Better Stories blog https://sccan.scot/1000-better-stories/1000-better-stories-blog/

Storytelling mini-grants https://sccan.scot/1000-better-stories/

Monday Jul 03, 2023

Monday Jul 03, 2023

Our Everyday Changemaker today is Ruth McLaren, Arran EcoSavvy's project and communications development officer.

Credits: Interview, recording and edit by Madeleine Scobie, Sound production by Kaska Hempel

Resources:

Arran Eco Savvy website: https://arranecosavvy.org.uk/

Green Islands Net Zero project: https://arranecosavvy.org.uk/green-islands-plans/

Project Videos

Zero Waste Cafe: https://vimeo.com/796376962/ce499f02e2

Active Travel Hub: https://vimeo.com/799647519/663c6e3da1

Community Shop: https://vimeo.com/826523465/3f3863284a?share=copy

Transcript

[00:00:00] Madeleine: Hello, I'm Madeleine Scobie and I'm SCCAN's media intern. I interviewed Ruth McLaren, who is the Project and Communications Development Officer at Arran Eco Savvy. Since 2014, Arran Eco Savvy has been working towards making Arran a greener and more sustainable island. Some other recent projects include the Green Islands Net Zero,

[00:00:24] Madeleine: the Active Travel Hub, Community Shop, and Zero Waste Cafe. I asked her to describe her favourite place to visit in Arran.

[00:00:34] Ruth: Ooh, that's a bit of a tricky question actually, because there's so many amazing places.

[00:00:39] Ruth: I'd have to say my favourite place is Glen Sannox in the north of the island.

[00:00:43] Ruth: And it's just this absolutely beautiful, kind of dramatic glen. Not too far from where I stay. And it's kind of really peaceful.

[00:00:51] Ruth: You often, you'll go from the beach, which will maybe have lots of people on it, and if you go up into the glen, it's kind of empty and don't see as many folk around, but you'll see, you know, deer. And I've seen a golden eagle in there once.

[00:01:04] Ruth: and it's just really just absolutely beautiful.

[00:01:07] Madeleine: So how did you get involved in Community Action? What's your climate journey?

[00:01:12] Ruth: I've always been very kind of interested and aware of climate change ever since I was at school, really. And it's just always been something that I've been very passionate about, but also very worried about.

[00:01:23] Ruth: And my career. I used to work, I've worked in the government, I've worked in the private sector, but I've also worked for several charities.

[00:01:31] Ruth: But I really wanted to get involved in climate action. And when I moved to Arran, I found out about Arran Eco Savvy, which is a local organisation. At the time, they were looking for a Shop Manager for their charity shop pre loved goods shop.

[00:01:45] Ruth: I applied for that job. I didn't get it, but then I subsequently applied for another job that they had advertised. And I've worked for Eco Savvy for almost five years now,

[00:01:54] Ruth: working across several different projects.

[00:01:56] Ruth: So yeah, I feel really lucky to have been involved to such a degree within the community and within such an impactful organisation within a community that is interested in climate change matters.

[00:02:07] Madeleine: So what's the biggest challenge that your community group or you had to overcome in taking action, and what do you think you learned from it?

[00:02:16] Ruth: I would say that the biggest challenge, just in general with both the community and the issue of climate change in general.

[00:02:25] Ruth: It's just such an overwhelming topic. It's something that affects all parts of life. You know, it's not just about, you know, the environment and you can be an environmental activist. It also connects with people's lives in terms of

[00:02:38] Ruth: the economy and their finances. You know, social issues and social justice. You know, lots of local issues, land use. You know, it really is, it really does connect with so many other issues that it's not just about, you know, climate change or the environment.

[00:02:54] Ruth: And I think that that's really the crux of the issue with the kind of slowness of change. In that, on these higher levels is that it's just people become so overwhelmed with talking about it. And it can be quite a negative thing also, you know, it's quite scary.

[00:03:07] Ruth: And that's not always easy conversations to have with folk.

[00:03:10] Ruth: And it's also not an easy thing for people to kinda think about.

[00:03:13] Ruth: And that's why at Eco Savvy, I think we kind of try to focus a lot of the time on the small things that people can do.

[00:03:20] Ruth: But also acknowledging that it's not just about individual change, it's about the wider community level changes, but also government levels and just acknowledging that it's something that intersects in all parts of everybody's life.

[00:03:32] Madeleine: What's something that you're most proud of?

[00:03:35] Ruth: I'm really proud of the work that the organisation does in terms of just seeing the everyday impacts that it has.

[00:03:42] Ruth: So for example, we were at an event at the high school in Arran a few weekends ago. And

[00:03:48] Ruth: we had our e-bike trials going on so people could come along and try an e-bike which are always super popular.

[00:03:53] Ruth: But we also had some kiddies bikes that have been donated. So, somebody wasn't using these bikes anymore, just handed them into us. And the mechanics had done them up and made sure they were roadworthy.

[00:04:04] Ruth: And then this wee girl came along and she couldn't ride a bike, but she really wanted to be able to ride a bike.

[00:04:09] Ruth: So our e-bike guy just spent 10 minutes with her and showed her how to ride a bike and then she could ride a bike. She was allowed to just take that bike home. So, you know, things like that on a community level that can have such a big impact for those individuals. And then a long lasting, you know, who knows what she might do, you know, once she's learned to ride a bike, that could make such a big change for her.

[00:04:30] Ruth: So these kinds of things, and it's the same with the food work that we do and the little pop-up cafes that we have. And within the shop, whenever you go in the shop, there's people coming in for a chat. People coming in to try eco products, to donate stuff because they don't wanna see these things wasted.

[00:04:44] Ruth: So really, yeah, I think the thing I'm proudest about the most is really kind of integrating into the community and the work that's been done there.

[00:04:50] Madeleine: Who or what inspires you?

[00:04:53] Ruth: So I think climate activists really, really inspire me. Nobody wants to be doing that stuff. You know, nobody wants to be taping themselves to bridges and gluing themselves to roads and things like that. Particularly the youth activists really, really inspire me because I just feel like, why should they have to think about these things?

[00:05:13] Ruth: It's so unfair, you know? It makes me quite bitter that they're having to think about these things, and not just think about these things but having to spend their time, you know, acting on these issues that shouldn't be a problem for them.

[00:05:25] Ruth: But having said that, it's so inspiring that they care so much and that they're really the ones leading the charge to kind of address the climate emergency. And yeah, I find that super inspiring.

[00:05:38] Madeleine: What do you think is the most powerful thing that the Arran community can do right now to help create a better and fairer future for all?

[00:05:47] Ruth: I would say coming together, the Arran community does generally come together really well, but coming together and just kind of doing more of what they're doing already, you know, and acknowledging that small actions can have a big, big impact. So, you know,

[00:06:02] Ruth: there's the stuff that we're doing with Eco Savvy with active travel and sustainable food, but it's kind of, people can do whatever they're good at. So if you're good at gardening, go along to your community garden and volunteer there.

[00:06:16] Ruth: You know, if you're passionate about the sea, there's an amazing marine conservation organisation here, so you can get involved with beach cleans or volunteer at the Visitor Centre at Coast.

[00:06:26] Ruth: You know, there's really so much on Arran that folk can do, and I think that people on Arran have a really special relationship with the place and the land and the landscape,

[00:06:37] Ruth: being an island that we are. Because we have all these issues with the ferries and things like that. But also it is a very amazing geographical place to be because you're on an island.

[00:06:47] Ruth: And when the weather's bad, you feel the weather and you feel the impact of the seasons. And you notice your environment a lot more than you perhaps might if you were living in the city. And I think that people in Arran are very aware of that and really passionate about preserving that and taking care of the environment and taking care of Arran and all these things. And I think that's really powerful.

[00:07:07] Madeleine: When I say Green Islands Net Zero. What's the first thing that pops into your mind?

[00:07:13] Ruth: Well, we have a Green Islands Net Zero project.

[00:07:16] Ruth: It has lots of levels to it. So on the biggest level, it aims to map

[00:07:20] Ruth: emissions of Arran to get an understanding of where our emissions can be improved.

[00:07:26] Ruth: And then on a

[00:07:27] Ruth: smaller level than that, it's also about making people's homes more efficient so that they are warmer and their bills are less. Especially during this cost of living crisis, I think everybody's certainly feeling the pain and the pressure of increased energy bills. So, I get that net zero can be a bit of a jargon term for folk and can be a bit off-putting.

[00:07:49] Ruth: But really on a basic level, it's about reducing waste and trying to make things more efficient so that yes, it's good for the environment, but it's also good for your pocket and that you save money in the process.

[00:08:03] Madeleine: What do you think is the most useful resource in terms of community climate action that you would point people to?

[00:08:10] Ruth: I'm gonna kinda cheat and say two. I think the best resource that you can have is having conversations with folk and learning about what's happening, having conversations about your opinions and what people that your friends and family have heard and their thoughts. But also I'm a massive fan of the internet and doing your own research, being on social media, just kind of being aware of what's happening around the climate change movement.

[00:08:39] Ruth: Because, you know, the mainstream media does report on it, but I think that there's a lot to be learned from smaller news outlets and blog posts and community organisations that are on the ground who are trying to deal with the climate emergency.

[00:08:54] Ruth: Who might have a lot more kind of progressive opinions and ideas and also have had experience and successes that are relevant to you wherever you are.

[00:09:05] Madeleine: What is your most treasured possession?

[00:09:07] Ruth: Well, I wouldn't really say it's a possession? but my most treasured

[00:09:11] Ruth: things would be my memories. So I would say all my life, basically, I've taken lots of photos ever since I was very young. So I would say all my photos that were physical photos that I have in photo albums. But then also now, the ones that I have that are digital pictures. I must have tens of thousands of them stored. So yeah, they would definitely be my most treasured possession.

[00:09:33] Madeleine: So if you could imagine Arran 10 or 30 years from now and imagine that we've all done everything possible to limit the effects of climate change and now Arran is a fairer and better place to be. Could you close your eyes and share one memory from that future with us?

[00:09:52] Ruth: The dream for Arran would be the community all living peacefully and happily together. But having much better local processes. So you know, we're able to grow our own food here. We're able to produce all the food that we need, or the majority of the food that we need here. Amazing transport systems where you don't need to have a car. Better off-road systems where the possibility of cycle lanes to link up villages. Just being much more resilient as well. And being able to function much more as a community with all the resources that we need as much as possible on our island.

[00:10:32] Ruth: I think that would be pretty ideal. And preserving the natural beauty of the island and keeping the air clean and the beaches litter free and plastic free.

[00:10:42] Ruth: All these fantastic things that we will have in 10 years time.

[00:10:47] Madeleine: Thank you for speaking to me about Arran Eco Savvy and also your own climate journey.

[00:10:51] Ruth: Thank you for having me.

[00:10:53] Madeleine: Check out Arran Eco Savvy's website to learn more about their different projects and the great work they're doing to create a planet friendly future for their island home. They've just published some short videos about their Zero Waste Cafe, Active Travel Hub and Community Shop, which are worth a look. The links for these are in the show notes.

[00:11:14] Madeleine: This is a little teaser for the upcoming Arran audio tour that we are hoping to put together as part of Everyday Changemakers. We will be recording some more interviews with other people from Arran Eco Savvy soon, so watch this space for more.

Friday Jun 16, 2023

Friday Jun 16, 2023

In the first episode of our Everyday Changemakers shorts series we meet Carolyn Powell from Huntly Development Trust who's working on community-led town centre regeneration.

Credits: Produced by Kaska Hempel

Resources

Trust Website: https://www.huntlydt.org/

Number 30/Town Centre development: https://www.huntlydt.org/what-we-do/town-centre

Carolyn’s bio https://www.huntlydt.org/about-us/people

New Economics Foundation https://neweconomics.org/

Climate Action Towns (Architecture and Design Scotland): https://www.ads.org.uk/resource/climate-action-towns

Climate Action Towns film: https://youtu.be/ZMj9PMrUwjs

Transcript:

[00:00:27] Kaska Hempel: Welcome to our Everyday Changemakers series. Wee blethers with everyday people taking climate action in their communities.

[00:00:38] Kaska Hempel: Hello, it's Kaska, one of your Story Weavers. Today's guest is Carolyn Powell from the Huntley Development Trust. She's been involved in a redevelopment of an iconic listed building in Huntley's main square. The Number 30, as it's affectionately known, is being transformed into a multipurpose community space with green credentials.

[00:01:01] Kaska Hempel: This project is a cornerstone of the trust's investment into community driven regeneration of the town centre. I caught up with Carolyn at Stirling at the May gathering for the Climate Action Towns project supported by Architecture And Design Scotland. She was one of the presenters in an aspirational showcase of towns taking a place-based approach to issues facing communities locally, including the climate emergency.

[00:01:30] Kaska Hempel: I started by asking her to describe the building she's been working on.

[00:01:37] Carolyn Powell: The building is in the middle of the town square, and what's wonderful about it is it's slightly magical. It has a tower at one end, and albeit that tower is not hollow, there's something about it that's reminiscent of a castle.

[00:01:54] Carolyn Powell: And you can imagine children making up stories about it, and it's on the corner overlooking, you know, right overlooking the square. So, as you come into the town, that's what you see. So, it makes the setting for something that magical that's going to happen. And hopefully with its renovation, something magical will happen.

[00:02:17] Carolyn Powell: I'm Carolyn Powell. I work for Huntley Development Trust and I'm Town Centre Development Manager. I work in Huntley, but I live on the coast just 20 miles away, half an hour from Huntley.

[00:02:28] Kaska Hempel: How did you get involved in Community Action? What's your journey?

[00:02:32] Carolyn Powell: I come from a semi-commercial background, but around about 2006 I began working for the New Economics Foundation and the interest that I'd had in regeneration was fuelled and I started working on different projects for them. One in particular was really a ground up approach to entrepreneurship. So, people in places actually turning their interests and their passions into work, into a job, and supporting them to do that.

[00:03:04] Carolyn Powell: So that's really where the drive comes from and the understanding that in any community there are people who can change not only their own future, but the collective future as well. And that is primarily driven by the desire and the passion to do something.

[00:03:20] Kaska Hempel: When I say place-based approach. What's your first reaction to it?

[00:03:26] Carolyn Powell: People. It's all about people. It must be.

[00:03:31] Kaska Hempel: And if you were to explain that concept to somebody that doesn't know anything about it, how would you explain it?

[00:03:37] Carolyn Powell: So, we have had periods in our history where we've designed around transport and roads and how things might look rather than people. People came second, they were put into that picture.

[00:03:51] Carolyn Powell: People are the picture, how they use the space. I mean, you wouldn't want a designer coming in to design your kitchen to come up with something that you, in practical terms, just simply couldn't use. And that's been what's happened in the past in some cases. So, places have not been fit for the purpose and the needs of the people that actually want and need them, whereas that's now being reversed.

[00:04:17] Carolyn Powell: So, we look at people first and we also look at what might happen. How might we want to do this? How would we want in the future, things to be different? You know, we might think that, okay, so we change this to make it more useful to people, to be more purposeful, but then we also build into that how we would like to build green space in the future.

[00:04:43] Carolyn Powell: We might not be able to do that right now, but if we change the traffic flow, if we have more people using sustainable transport rather than individual transport, we might then be able to create more green spaces. So, we need to think ahead with those things as well.

[00:04:58] Kaska Hempel: What was the biggest challenge that your community group or your project had to overcome, and what lessons you've learned from that that you can share with people?

[00:05:08] Carolyn Powell: Probably the communication of it because there are so many strands to it. There's no single sound bite that will, you know, answer the question as to how it's been designed, how it can be used in the future. And the way that so far, and this will continue because it's obviously it's not quite finished, to get around that has been actually bringing people into it.

[00:05:32] Carolyn Powell: Even during the building process so they can start to see. Well, it's taking so long because the thing is falling down, and they could see that for themselves. And then later on they can see the spaces, oh gosh, you know, we can use that space and that space and oh, there's a staircase there, and oh, there's a lift over there, you know, and suddenly it's a real thing.

[00:05:51] Carolyn Powell: But communication's quite a tricky one because small pieces of information invite criticism and yet you can have too much information where it's changing, so it's very hard to keep that momentum going with it.

[00:06:06] Kaska Hempel: Who or what inspires you?

[00:06:10] Carolyn Powell: Actually, this is going to maybe sound a little strange. Change inspires me.

[00:06:16] Carolyn Powell: Everything is in a constant state of change and change is a good thing because you can't renew without change. Without change, things die. And that kind of resistance to it is, you know, it's so complex. But we need to embrace change. Now that's assuming all change is good, but of course, some change isn't necessarily.

[00:06:43] Carolyn Powell: But change inspires me because it can make things happen. It can stir things up, it can, you know, it can activate and inspire and really trigger something.

[00:06:56] Kaska Hempel: What is your most cherished possession?

[00:06:59] Carolyn Powell: His name's Angus. He has four legs and a tail. And in order to come here today for the very first time last night, he went to kennels and tomorrow morning I pick him up.

[00:07:10] Carolyn Powell: So yes, he is without doubt my most treasured possession. I shouldn't say a dog's a possession. If it was an actual physical thing, I dunno what it would be. But certainly there's a couple of things, handmade items from, you know, children's collection I probably would grab. It's just a demonstration of where they were at at that point and how you felt at that point.

[00:07:33] Carolyn Powell: And sometimes physical items encapsulate that. It's about like any memory that's connected with something tangible. It just evokes the memories of that period of time.

[00:07:45] Kaska Hempel: If you could imagine Huntley or the project or descend of town in 10 years time or 30 years time. And if you could just close your eyes. You can spend a second thinking about that, and I'll ask you for one single memory from the future that you could share with us about this place.

[00:08:04] Carolyn Powell: So, I live half an hour away, so I've just gone there. And the first thing that I'm struck by is the number of people that are actually walking through the middle of town.

[00:08:18] Carolyn Powell: That's because they can, because the traffic's now been diverted and it suddenly looks green, so it doesn't look all grey because the building's obviously there, greyish in colour. But it looks quite green because there are these trees in the centre and there's places to sit and people are chatting and there's tables and chairs outside Number 30, and there's tables and chairs outside the bookshop and people are sitting and they're chatting.

[00:08:43] Carolyn Powell: Older people are chatting to young people. The youngsters are coming through from school, but instead of heading straight down to get, you know, different types of hot food. They're stopping to say hello to people in the town, not just in their groups, and they're going into different places and they look cheerful.

[00:09:03] Carolyn Powell: And there's a feeling of excitement. It sounds chattery busy. But not bus driving through the middle busy. So, it's quite a different feel. There are some rather lovely smells because there's the smell coming from the lovely Bank Restaurant, which now exists. And there's different smells coming out of Number 30.

[00:09:27] Carolyn Powell: And in the corner, there's somebody baking bread somewhere. And there's notices about things that are happening, that people are being invited to. So, yeah, I don't need to shut my eyes for that one. That's real.

[00:09:38] Kaska Hempel: Is there anything else that you'd like to share with 1000 Better Stories podcast listeners?

[00:09:44] Carolyn Powell: It's not an easy thing. And people can give up because it is tough and, you know, make no bones about it. But I think the most important thing is don't lose sight of these dreams. And, you know, if there was a criticism of the way we've all been in the past, it's not that we've been over ambitious and failed, we haven't been ambitious enough.

[00:10:07] Carolyn Powell: Be really, really, really ambitious. What have you got to lose? Just do it.

[00:10:16] Kaska Hempel: Check out an excellent blog on Huntley Development Trust's website for more stories about Number 30 and other wonderful work they're doing to make their town better for everyone. And if you are interested in finding out more about the nine towns involved in Climate Action Towns Project, I highly recommend the short film by Bircan Birol, which is available on ADS YouTube channel. I've put the links in the show notes for you.

[00:10:42] Kaska Hempel: As you might have noticed, Everyday Changemakers is a new format we've introduced for 1000 Better Stories podcast to help us showcase more of the amazing work done by communities across Scotland and show that everyone can make a difference. Let us know if you'd like to share a story of a changemaker in your own community, and we'll arrange for an interview with one of our field reporters, or maybe you would like to interview someone yourself.

[00:11:08] Kaska Hempel: We are planning training in audio recording and editing soon. If you're interested, get in touch with me on stories at SCCAN dot Scot. Until next time, keep making a difference out there.

Monday May 29, 2023

Monday May 29, 2023

We share an episode from Collaborative Mobility UK podcast channel. CoMoUK is the national charity dedicated to the social, economic and environmental benefits of shared transport. Among many other things they provide excellent support and resources for community groups wanting to set up shared car or bike clubs.

The story explores some of the opportunities and challenges faced by community car clubs, and features three guests speaking about their experiences running a car club and navigating challenges including insurance, pricing, and sustainability:

Malcolm McFarlane from Kinross-shire Movegreener in Kinross, Scotland

Mike Callaghan from Local Energy Action Plan (LEAP) in Lochwinnoch, Scotland

Andrew Capel from Llani Car Club in Llanidloes, Wales

For more stories from CoMoUK, see their Shared Transport Podcast on podbean: https://comouk.podbean.com/. You can also find it on all main podcasting apps.

Credits: Produced by Paul Bristow for CoMoUK

Resources

CoMoUK website: https://www.como.org.uk/

CoMoUK Shared Transport Podcast: https://comouk.podbean.com/

1000 Better Stories episode: An honest look at one community’s car and bike clubs about the Porty Community Energy project https://www.podbean.com/eas/pb-bz9wn-1387976

Car-shares

Movegreener: https://www.movegreener.org/

Local Energy Action Plan (LEAP): https://www.myleapproject.org/

Llani Car Club: https://www.llanicarclub.co.uk/

Porty Community Energy: https://portycommunityenergy.wordpress.com/

Friday Apr 28, 2023

Friday Apr 28, 2023

What can we learn from the multigenerational wisdom of Gaelic tradition bearers about reconnecting our communities to places where we live, to our past and to our future in the changing climate?

To explore these questions, Our Story Weaver, Lesley Anne, talked to Gaelic Officer for CHARTS, Àdhamh Ó Broin, about his journey into Gaelic tradition-bearing and activism, the role of land-based ritual in modern world and seven-generation thinking.

The interview was inspired by the Spring equinox event, “Dùthchas Beò revitalising reciprocity with the Gaelic landscape”. This took place at ancient sacred sites of Kilmartin and Knapdale in Argyle and was a collaboration between Àdhamh and SCCAN’s network coordinator for Argyle and Bute, Marie Stonehouse.

Resources:

CHARTS https://www.chartsargyllandisles.org/

Dùthchas Beò event https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/556630325287

Gaelic pronunciation https://learngaelic.net/dictionary/index.jsp

“The Good Ancestor – How to think long term in short-term world” by Roman Krznaric https://www.romankrznaric.com/good-ancestor

“Body Keeps the Score” by Bessel van der Kolk https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/18693771

Transcript:

[00:00:36] Kaska Hempel: Hello, it's Kaska, one of your Story Weavers. I'd like to take you to one of my favourite places in Scotland, Kill Martin Glen in Argyll. Imagine it's an early spring afternoon and you're standing at the wide bottom of a shallow glen surrounded by gentle hills. Dotted with trees on the verge of bursting into leaf.

[00:01:01] Kaska Hempel: Birds fleet around in their branches and chatter with the spring excitement. You listen for the trademark territorial cuckoo calls, but they've not made it back from Africa yet. They'll be along in May, together with the blue bells. The sound of cars passing through the village breaks through the nature's spring soundscape, but it comes back even stronger after every wave of traffic.

[00:01:26] Kaska Hempel: You look down the wide grassy glen and the skies moving medley of blue and the gray cloud. The sun hits your face with a fleeting kiss as the shapes shift above your head. In front of you is a circle of standing stones manmade, but they've somehow become part of the landscape covered in colourful mosaic of lichens.

[00:01:50] Kaska Hempel: The more than 350 similar ancient monuments within a six mile radius of this village, with 150 of them prehistoric standing witness to more than 5,000 years of human history of this place. Your bare feet sink into cold, wet grass, and it feels like this place along with all the generations who'd passed through it is embracing you like a long lost friend.

[00:02:18] Kaska Hempel: This is how I imagined the setting of Dùthchas Beò, a Spring Equinox event, which took place at ancient sacred sites of Kilmartin and Knapdale. It explored a revitalizing reciprocity with a Gaelic landscape. It was a collaboration between the Gaelic Officer Àdhamh Ó Broin from Argyll and Isles Culture, Heritage and Arts organisation, and SCCAN's Network Coordinator for Argyll and Bute, Marie Stonehouse.

[00:02:46] Kaska Hempel: So what can we learn from the multi-generational wisdom of Gaelic tradition bearers about reconnecting our communities to places where we live, to our past and to our future in this changing climate? To answer these questions, our Story Weaver Lesley Anne talked to Àdhamh about his journey into Gaelic tradition bearing and activism, the role of land-based ritual in modern world and seven generation thinking.

[00:03:14] Kaska Hempel: But before we go any further, I would like to profusely apologize for my Gaelic pronunciation in this introduction. I'm a complete novice at this. Now, to start us off, Àdhamh introduces two concepts at the core of Gaelic identity and culture.

[00:03:32] Àdhamh Ó Broin: Dùthchas, which is the name of the event. Dùthchas Beò. Dùthchas, coming from the concept of dùth, which is an old word for people, and dùthaich, which is country. Land that is inhabited by people and therefore dùthchas is that inimitable connection with the place where your people have sprung. Now, for me though, this is quite difficult to articulate fully. Because I don't have a great sense of dùthchas with the place that my people came from because they're all gone.

[00:04:07] Àdhamh Ó Broin: They're all either cleared or forced to leave through economic circumstance. And I've been getting back up to my mother's area in, in Latheron Parish, in Caithness and getting my bare seat in the ground and trying to encourage the dùthchas to return to me there. And I've been doing the same in Ireland as well. But Argyll, the area that I grew up in, in the area that I'm probably most well known for being a tradition bear in, I don't have any ancestor connection to, so I've been adopted by the land there.

[00:04:36] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I feel very, very welcome there and I feel respected and appreciated by the land, by some people in the area. But for people who perhaps let's just see, you know, your from the Isle of Barra. And you know, you can trace back several generations on all sides. And so you and your people have always been from Barra. Then that sense of dùthchas is incredibly strong because you not only still inhabit the land of your ancestors, but you can trace the movements of your ancestors, you know, right across the landscape.

[00:05:05] Àdhamh Ó Broin: So that's the dùthchas thing. It's ancestral relationship with land and feeling of connection with it. So if dùthchas is the land and your relationship with it and your right to remain on that land and being in relationship with that land, then dualchas is the manner in which you described that relationship. So dualchas is you know, your stories, your songs, your Proverbs, your local history, all that side of things.

[00:05:27] Àdhamh Ó Broin: But it's specifically that which is inherited from generations before you. You know, so dùthchas is the land and your relationship to that and dualchais is the stories of the consistent relationship with that land as told by your ancestors. So they're utterly crucial to the, well, my name's if I was to introduce myself in sort of Ancestral styles you might put it in Is mise Àdhamh, mac Sheumais bhig, 'ic Sheumais mhóir, 'ic Diarmuid, 'ic Sheumais, 'ic Mhurchaidh, 'ic Sheumais.

[00:05:58] Àdhamh Ó Broin: That's referencing seven generations of my father's line and all the way back to Wicklow in Ireland. And so I suppose that if you're referencing seven generations back and honouring your ancestors, that far back then you're kinda making a commitment to be a good seventh generation. If we're lucky enough to get to that stage with the state things are in, but you know, so, that's who I am in the Gaelic sense in terms of professional end of things.

[00:06:28] Àdhamh Ó Broin: My work goes from very organic tradition bearing, picking up things that are about to get lost and keeping them and hopefully passing them on. So that's culture, songs, stories, Proverbs, anecdotes, words, idioms. It goes from that right across to consulting on films. At the moment, is mise Oifigear Cultair Ghàidhlig, i'm Gaelic Culture officer at CHARTS Argyll and the Isles, so we're a member led arts organisation and in that I have remit for Gaelic culture.

[00:07:07] Lesley Anne Rose: I mean, that sounds like one of the best jobs in the world, but you've also got the role of a tradition bearer. I'd love it if you could share a little bit more about what that role actually involves, and how, if anything, your journey to becoming a tradition bearer is in any way linked to your climate change journey.

[00:07:24] Àdhamh Ó Broin: Yeah. I'd always been environmentally focused since I was a child. You know, I think like anybody else with their head on straight, you know, they have spent a reasonable amount of time watching David Attenborough as a child, you know? So, you know, it came from that. And I remember there was a programme called Fragile Earth.

[00:07:41] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I used to watch that every time it was on, and I was sort of ethically vegetarian, you know, was brought up that way with my father, in fact. Growing up and I just always had one eye on that. Grew up in the country and just felt intrinsically connected to nature and it was bonkers that they were mistreating it. I mean, it just didn't make any sense whatsoever.

[00:07:59] Àdhamh Ó Broin: My father's people are all Irish, my mother's folk are predominantly from Highland Caithness, although I grew up in Argyll so a wee bit of a kind of Gaelic mix there. Highlanders and Irish folk are essentially one people, the Gaelic people, and folk from the Isle of Man as well. So it's really, it's an ethnicity, you know, and it happens to now be

[00:08:14] Àdhamh Ó Broin: quite divided by geopolitical boundaries, but the vast majority of people on the ground in the Highlands and Islands saw themselves as Gaels you know. But I never got that immediate everyday sense of who I was. I'm not a first language Gaelic speaker. As a child growing up in Cowal, I didn't have the language or culture passed down by my parents, but was very strongly encouraged by my only grandmother to pick the language of our people back up.

[00:08:44] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I came home to there after 10 years in Glasgow, and found that the language is on its very, very last legs, local dialect in central Argyll. And so I began to, as I said before, collect all these things that were getting lost and interviewing old people, some of whom couldn't speak the language fluently, but had loads of memories of it being spoken in words and praises and all sorts of things.

[00:09:11] Àdhamh Ó Broin: And then I brought up my children, with myself, my wife and three kids, all of them are fluent Gaelic speakers. And myself, my wife. Our three. Our first language speakers. I've never spoken any English in the house to them, so that means that the dialect of central Argyll is a living language once again, even though all the native speakers have unfortunately now passed away.

[00:09:33] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I suppose what happened was that. Because I had to struggle so hard to get the language back. I mean, not that it was difficult learning it, it felt like just placing bits of the jigsaw puzzle back into my brain, you know where they belong. Back into my soul. But you know, it's still challenging to do that with a young family and working and all the rest of it.

[00:09:51] Àdhamh Ó Broin: So as the years rolled on, that momentum of learning the language never left me. Once I had the language fluently, then I started going around the Highlands and, and recording, you know, tradition bearers and recording the dialects that were dying, you know, and many of my friends, my old friends and in different glens and islands and what have you have now passed on.

[00:10:16] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I'm very thankful to them for holding onto the language long enough for me to be able to learn it from them. But, I don't have that sense of intergenerational transmission. And so it's been a sense of rather than just what's normal and, you know, been happening for generations, it's been a sense of urgency and necessity that's caused me to tradition bear.

[00:10:35] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I saw a lot of things that were being lost, as I said, and I didn't see anybody else holding onto them, and I saw they were about to go, you know, and you're talking about spruilleachd, it's like, you know, almost like the crumbs that are left after you've touched yourself a slice of bread. You know, the breads actually long gone, but these crumbs are still there.

[00:10:54] Àdhamh Ó Broin: And if you pick them up, you can more or less sort of, you know, get a chewable bite out them, you know. And that's I suppose what tradition bearing is all about in a minoritized culture that is, you know, lost sort of 95% of its richness and speakership. So, tradition bearing for me is something that I've stumbled into backwards in an accidental fashion and now realize that I'm a tradition bearer and now realise that there aren't that many people like me, especially in the mainland, and it's almost like you're gathering up all the family photographs as you run outta the burning house, and then you're standing outside them all and suddenly you're the keeper of the photographs. But actually, you know, you hadn't even looked at them in 20 years, you know, and suddenly it's like, well, these are really important because everything else is gone.

[00:11:40] Àdhamh Ó Broin: Ultimately, if they're valuable things, somebody needs to pick them up and safeguard them.

[00:11:46] Lesley Anne Rose: That's lovely. There's so much sort of vivid imagery that you've shared with us. Thank you. That phrase you used about, I came to it backwards. I would just like to pick that a little bit more in relation to climate change.

[00:11:56] Lesley Anne Rose: Partly from interviewing someone up in Skye who is also a tradition bearer and they used the really beautiful metaphor or analogy that tradition bearing is the same as rowing a boat. Although you are, you are going forwards, but all the time you are looking backwards. And they were very keen to impress that tradition bearing isn't something that's about sort of stuck in the past about old sepia photos. It is very much a role that has a responsibility to look forwards as well. And just again, in terms of that sort of, onus around climate and looking after the land and tradition and people, how do you see that role of a tradition bearer in safeguarding the future, if you like, as well as the past?

[00:12:37] Àdhamh Ó Broin: Yeah, it's a great question. And I would agree strongly with the person that you'd spoken to there. I would just add that I'm not scared to look back to the past. I think in the modern world, people, they almost feel like they need to virtual signal about technology to say we are okay with technology.

[00:12:52] Àdhamh Ó Broin: Yes, we are grasping it all. Yes, we want it all, we're not against it. But you see, as anybody who's aware of environmental degradation, we know that technology in and of itself is not necessarily a good thing unless it is weighed up with the potential consequences and ramifications of its overuse.

[00:13:07] Àdhamh Ó Broin: We know that from the industrial revolution. You don't have to constantly convince people that Gails aren't old quarry people in sweaters, you know, stuck on crofts who never ever go anywhere else. We, you know, we know that's not true, but that comes from a long, long period of internalized colonialism. And you know, people were told it was holding back and told that, you know, if you were from the Highlands and Islands, you're just a daft Teuchter and all the rest of it.

[00:13:31] Àdhamh Ó Broin: You know, it's inbuilt in people so I understand it, but I think we need to get away from it. It's actually ok to value old things and it's okay to think for some people to feel much more comfortable with old things and older people and older traditions than they do with a lot of the traps in the modern world.

[00:13:49] Àdhamh Ó Broin: I'm certainly one of them, you know. So in terms of the environmental connection though, I don't believe climate change is happening or there's nasty things going on with the environment in the world. Because if anything that I've been told in a top down fashion by, you know, academic institutions or governments or organisations, I believe that there's something fundamentally wrong with the natural patterns in the world because our lore doesn't fit the weather anymore.

[00:14:19] Àdhamh Ó Broin: That's why I believe it. You look at phrases and things used to describe the weather that have been in place for decades, if not centuries, if not longer than that, and they don't fit anymore. There's one, for instance, you know,